Line Infantry

Line Infantry

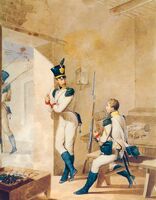

"During the campaign [of 1814] the Austrian soldiers were in the habit of exclaiming that the Neapolitan infantry and the Austrian cavalry were always sure of victory."

The Line Infantry formed the bulk of the Neapolitan army and were those who decided definitely whether a battle was won or lost.

Overview |

|

Line Infantry was the main fighting arm of the Neapolitan Army. It was the basic, hardened core of the armed forces, made up of both experienced veterans and fresh recruits; as Napoleon himself once said, it was the “sinews of the army”. As in the Grande Armée, it was the most numerous branch, at its peak being able to muster thirty-six battalions split into twelve regiments. The basic principle of Line Infantry was to fight in formed, compact masses, to batter enemy troops with thunderous volleys of musketry, and eventually to charge and take positions at bayonet point. The formations mainly used by French and allied line infantry was the line, the column, and the square. Terrain, weather, and the quality of enemy troops each defined what formation a commander was to use: for example, in Spain, Neapolitan line regiments generally fought in column when fighting formed bodies of troops, as the Spanish infantry was generally of inferior quality. In 1815, Neapolitan troops fought on many occasions in line against experienced Austrian troops, as at Carpi, Spilimberto and Tolentino.

|

| |

|

The Neapolitan Army’s infantry tactics and drill were almost entirely based off the French 1791 Réglement, which posed as a sort of handbook for unit commanders. It defined the entirety of a regiment’s drill and formations, including the placement of officers along the line, the way a regiment wheels or turns in action, and the evolutions of a line during battle. The formed line was the most basic battle formation for infantry. By standing in two to three-rank deep lines, a battalion could theoretically use the maximum firepower possible. French regiments and their allies in particular used three-rank lines: while the first two fired, the third would pass along their muskets for their comrades ahead to use, while reloading empty ones. When a company was reduced to below 12 files, it would form two ranks. However, marching and manoeuvring in line was complex and required great concentration – in rugged or uneven terrain, lines regularly fell into disorder, especially with inexperienced troops. For this reason, many Neapolitan attacks in Spain were done in column formation, which was easy to maintain in order and could generally move faster without losing cohesion. The melee power of a column was also greater than that of a line, as it applied maximum pressure to a single spot of the enemy line. French and Neapolitan commanders frequently mixed these two formations together, in various circumstances. At the Ronco in early April 1815 the Neapolitan infantry advanced formed up en marteau, or like a hammer. This mixed a deployment of columns behind a line, similar to forming in oblique order. At Tolentino, D’Aquino’s division formed itself into monstrous regimental squares, the sides formed up in column and the front and back formed in line. Similarly, at Cardedeu, the main French attack consisted of huge columns of lines, which succeeded in penetrating the Spanish defensive positions. Neapolitan Line regiments also frequently fought in open order, or as skirmishers. While this usually was the task of the volteggiatori, the nature of guerrilla warfare put solid formations at a significant disadvantage to fast-moving shooters hiding among trees and rocks; hence, in several cases, Neapolitan companies and platoons deployed openly, using cover and firing at will. Recruitment for line regiments was the least exclusive in the Army. While there were many volunteers joining the armed forces, the majority of these were drawn to the cavalry by their flashy uniforms and élan. The regiments of the line had to contend with largely unmotivated conscripts and draftees taken from prisons, which resulted in high rates of desertion. Bigarré, Colonel of the 1st Line, mentioned in his memoirs how he had to keep his conscripts “chained like convicts” on the march to the regimental depot to prevent them from escaping and deserting. Nevertheless, once trained, the Neapolitans made good soldiers, especially in skirmishing. Many veterans of the line regiments would then prove their worth again in the 1815 campaign, as part of the Royal Guard. |

I'm Interested In |

|

|

Related Pages | ||||||

|