Line Cavalry

Cavalry of the Line

“Colonel Zenardi, at the head of the 1st Regiment of Chasseurs à Cheval, has become the terror of the insurgents…” – General Duhesme

Overview |

|

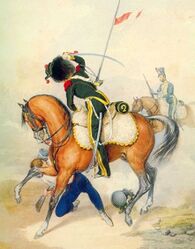

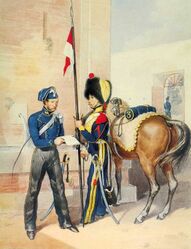

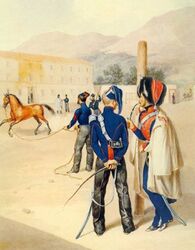

Line Cavalry was the term that defined the regular regiments of the Neapolitan mounted arm. They were the core of the cavalry, and were almost always thrown into battle (unlike the Guard cavalry, which was frequently held back in reserve). Initially, they numbered two regiments of Horse Chasseurs, which would prove themselves invaluable in hunting down insurgents in the Tyrol and Spain. These would be expanded to include a regiment of Chevaulegers in 1810. In 1813 all the regiments were converted to Chevaulegers-lanciers, and a fourth regiment came in 1814. The basic principle of Line Cavalry was to act as the eyes and ears of their army corps. As light cavalry, they rarely engaged in combat during pitched battles, as their shorter mounts and curved sabres made them generally inferior to the larger medium or heavy cavalry regiments, such as dragoons or cuirassiers. Hence, their task was primarily to form the advance-guard, harrying the retreating enemy, fighting off skirmishers, gathering intelligence, and only in crucial moments would they be ordered to charge formed masses of enemy infantry or cavalry. They would typically held back from striking a decisive blow in battle, although there were cases when chasseur and hussar regiments joined in on the charges of their heavier counterparts. In Spain, the quality of both Spanish infantry and cavalry was generally inferior to that of their French counterparts; the Neapolitan cavalry hence had almost free reign in picking their opponents. Furthermore, the scattered insurgent bands were hugely vulnerable to cavalry action, especially in open terrain. This gave the Chasseur regiments excellent opportunities to gain laurels. The first two Neapolitan line cavalry regiments were formed in early 1806, from men taken from the old Bourbon cavalry regiments and a number of volunteers. They were probably the quickest units to be fully formed, as men were always eager to join the flashy mounted units as opposed to the mundane foot regiments. The regiments were designated as Cacciatori a Cavallo, the Italian equivalent of Horse Chasseurs. While not as glamorous as other types of cavalry, they still possessed the famed light cavalry espirit de corps that enabled them to perform feats of extreme bravery in combat. |

| |

|

"Cavalry should be seen as the eyes and legs of an army. Through the different functions it is obliged to fulfil, speed and lightness are the qualities that must be sought after in its organization." - Marshal St. Cyr, Thoughts on War.

French commanders in the Peninsula understood how to use light cavalry well. The 1st and 2nd Chasseurs almost always fought in the advance guard in close support of the light infantry, proving hugely successful in riding down retreating insurgents after the end of a firefight. They frequently operated with the 1st Light as the first units of the advance guard. Their success led their division commander, Pignatelli-Strongoli, to write: "The entire army corps thinks that there are no better light horsemen than the Neapolitans.". On the contrary, the Neapolitan line cavalry also served in conventional battles, in Germany and in Italy. The 2nd Chevaulegers would serve in Germany in the battle of Bautzen and in numerous small actions against formed troops; in one instance, they forced a Prussian battalion to retreat with loss. Unfortunately no more cavalry regiments were sent from Naples to the Grande Armée, notwithstanding the critical shortage of trained light cavalry on the French side. In 1814 the cavalry would act frequently as scouts but would not be engaged in any serious actions, given that the Austrian cavalry was more numerous and of better quality. This latter trait would become painfully visible in the 1815 Campaign. The Neapolitan lancers would have significant trouble fighting off the wily Austrian hussars, many of them veterans of Austerlitz, Wagram and Leipzig. Although no large regiment-to-regiment combats occurred, there was one notable instance in which General Napoletano's cavalry division (composed of all the line cavalry regiments) routed the Austrian advance guard near Senigallia by first overthrowing the Austrian hussars and then breaking and capturing an enemy square. At Tolentino the Neapolitan chevaulegers captured a retreating battalion of Tyrolean jaegers, alongside two pieces of artillery. It is said that they even managed to briefly capture General Bianchi, the Austrian commander-in-chief, but were forced to abandon their prisoner after being counterattacked by his escort. |

I'm Interested In |

|

|

Related Pages | ||||||

|